"I Cannot Read a Sealed Book"

Joseph Smith, Charles Anthon, and Isaiah’s Sealed Book

Note: This essay begins with a stylized retelling of Isaiah’s vision.

“Ariel” was in trouble.

The city’s walls were buttressed by siege works, food and water were running low. Jerusalem’s enemy had her in a chokehold.

They would, anyway… in the near future. It wasn’t really Isaiah’s place to speculate when, exactly. His job was to warn the people.

But, unfortunately, no one seemed to care.

Feasts came and went, month after month, like clockwork. The people offered sacrifices, prayed to God, followed Torah. Not because they truly cared; religion was just an insurance policy. They thought if they could impress God enough with their performance, he’d save them (if it came down to that).

That turned out not to be the case.

Isaiah had seen Jerusalem’s destruction in a vision. So why didn’t they see what he saw?

The ancient prophet’s answer was simple:

“For the Lord hath poured out upon you the spirit of deep sleep, and hath closed your eyes: the prophets and your rulers, the seers hath he covered” (Isaiah 29:10).

Even if the people wanted to open their eyes and see God’s judgment coming, they couldn’t.

Isaiah likened the vision of Jerusalem’s imminent destruction to “the words of a book that is sealed” (Isaiah 29:11).

“Read this,” said the prophet, gesturing toward the sealed vision.

A man in fine robes stood before Isaiah, the kind of guy you could tell was intelligent. The man took the book. He studied the outside, circled the wax seal beneath his thumb... then handed it back.

“I can’t,” he said. “It’s sealed” (see Isaiah 29:11).

Isaiah turned, and found another man. This one in coarse linen, hands worn from manual labor. The prophet held out the book.

“Read this, please.”

“I can’t even read,” the man shrugged without taking it (see Isaiah 29:12).

The metaphor was clear enough. The prophets—the fine-robed guy—were the ones who should have seen, but couldn’t, because God had closed their eyes. And the seers—the illiterate guy—were the ones who couldn’t even read to begin with, because God had covered their heads.

No one could see the judgment coming.

Centuries later, in western New York, a young man named Joseph Smith sits reading these very words. As his eyes move across the familiar passage, something stirs his imagination. The ancient scene shifts: the book, the scholar, the unlearned man. They’re all reimagined in modern roles.

“‘I cannot read a sealed book,’” repeats Joseph, closing the Bible in his lap as his eyes drift to the man sitting near him. “Is that really what the professor said?”

“That’s precisely what he said,” answers Martin Harris.

Joseph’s eyes drift to a cloth-draped bundle on the table nearby. It’s 1828, and the two men sit quietly in the room where Joseph will soon begin dictating what would become Mormon scripture. In just a few months, they’ll have 116 pages completed.

But, according to Harris, Professor Charles Anthon couldn’t make out a single character.

In Joseph’s mind, Isaiah’s prophecy had truly come to pass. Just as before, the sealed book was delivered to a learned man (a trained linguist) who couldn’t read it, “for it is sealed” (Isaiah 29:11). But unlike “him that is not learned” (Isaiah 29:12), Joseph, untrained and uneducated, was translating by “the gift and power of God.”

Years later, Joseph couldn’t help but see himself in this passage:

“I commenced translating the characters and thus the Propicy of Isiaah was fulfilled which is writen in the 29 chaptr concerning the [sealed] book.”1

In his hands, Isaiah’s warning to ancient Jerusalem became something more: a prediction of a sealed book, a learned man, and an unlearned prophet in New York.

The Scholar and the Scribe

The story of the Mormonism’s gold plates has always fascinated me. According to Joseph, there were, for centuries, ancient records of God’s people in the Americas lying dormant in a hill in rural New York. Then, on September 22, 1827, he unearthed them with the help of an angel. Over the course of two and a half years, Joseph claimed to have translated the text in fits and starts, finally publishing it in March 1830 as the Book of Mormon.

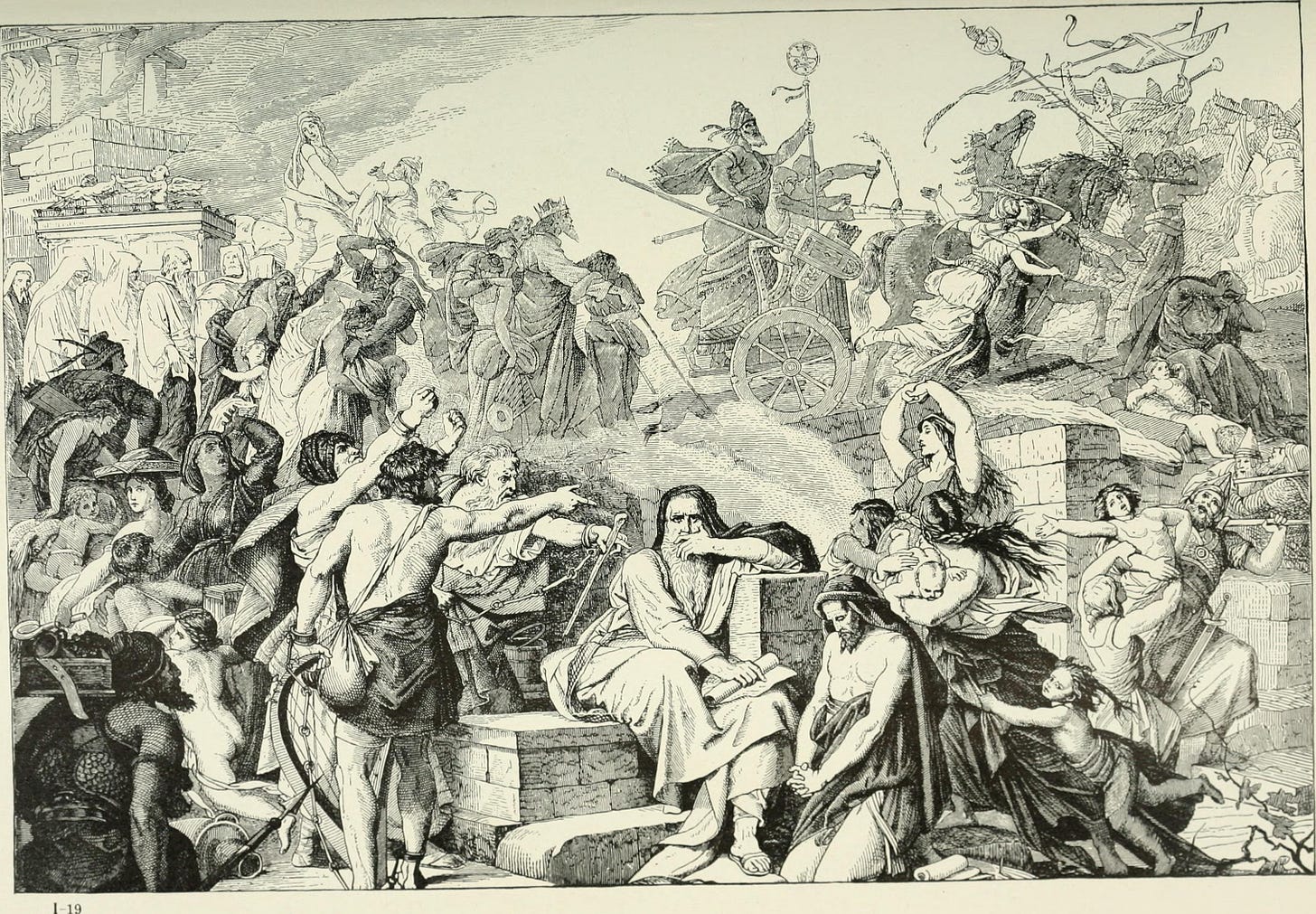

Joseph claimed to translate the plates by the ‘gift and power of God,’ but early on, he also made attempts to understand and replicate the strange etchings himself, a language he called “reformed Egyptian.” Having barely studied his own native English, he thought it best for a linguistics expert to at least validate the authenticity of the characters on the plates, even if experts couldn’t translate it. So, he transcribed a small set of characters and entrusted the document—titled “Caractors”2—to his benefactor-scribe, Martin Harris, who traveled to New York City in search of Professor Charles Anthon, “a promising young classicist” who had been teaching Greek and Latin since 1820.3

What happened next depends on who you ask.

According to Harris, Anthon examined the characters and affirmed their authenticity: the text was written in “Egyptian, Chaldeak, Assyriac, and Arabac.”4 Anthon even gave Harris a written certificate validating them. But when Harris explained the origin of the plates—about how an angel delivered them to an barely-schooled farmboy—Anthon tore up the certificate and declared it all a fraudulent ruse. He offered to translate the plates himself if Harris could bring them to him, but Harris replied that part of the plates were sealed. At that point, Anthon allegedly said, “I cannot read a sealed book.”

*cue Isaiah 29*

Harris’s account was later canonized in LDS scripture (Joseph Smith—History 1:63–65), and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints naturally favors it, portraying Anthon as the scholar who “certifie[d] characters and translation from plates.”5

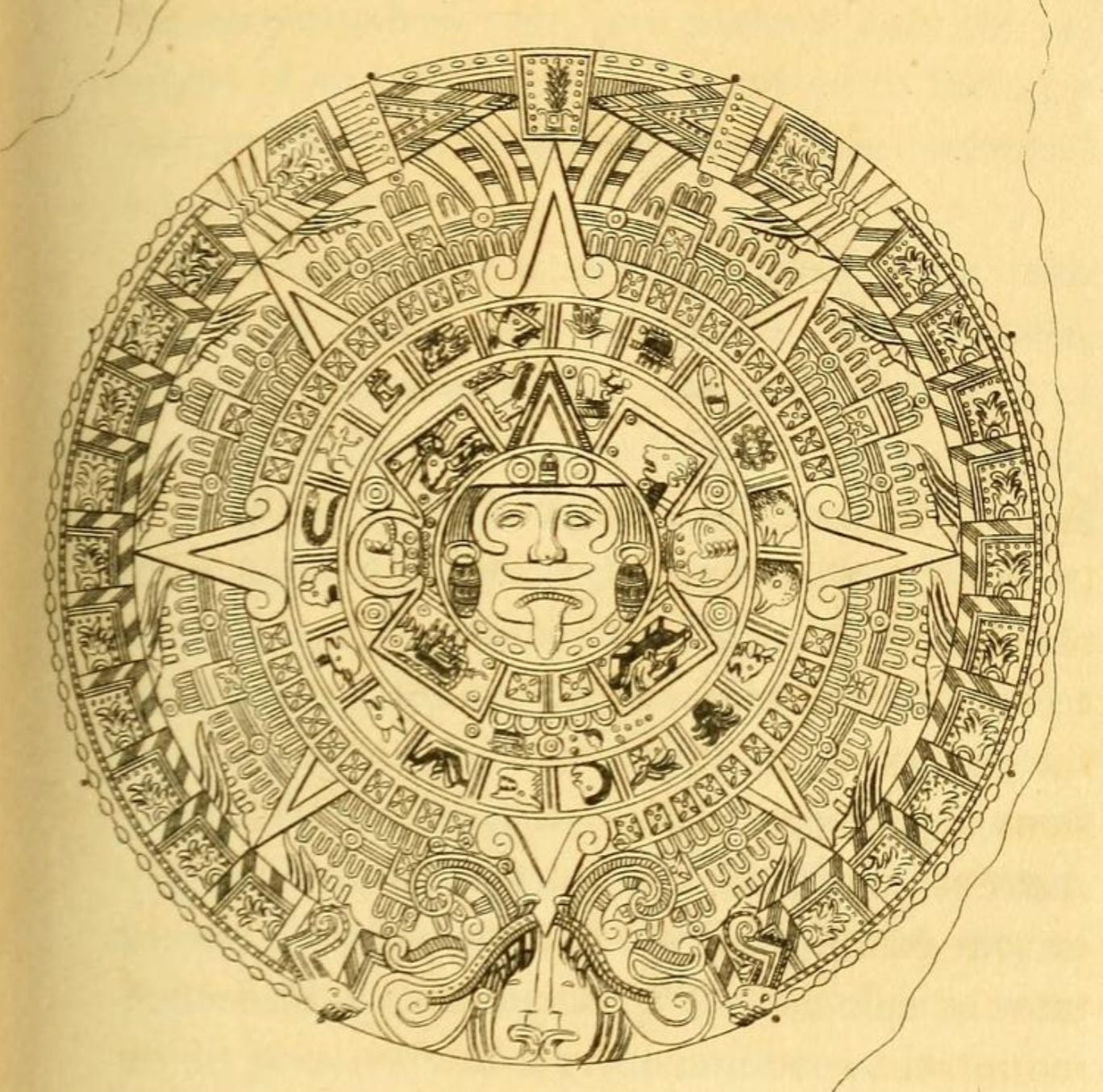

But according to Anthon, Harris’s story was “perfectly false.”6 The professor claimed he was approached by Harris with a sheet of gibberish—“Greek and Hebrew letters, crosses and flourishes, Roman letters inverted or placed sideways.”7 Anthon even saw what he thought was a “Mexican Calendar” from an 1814 textbook.8

Anthon’s comment led scholar Sonia Hazard to wonder whether the plates were real, but taken from printing plates etched with a medley of reversed letters, symbols, and illustrations such as stars, half-moons, and concentric circles, which resemble characters from copper or stereotype plates used for early 19th-century printing presses.9

At any rate, Anthon feared it was “all a trick, perhaps a hoax,” and warned Harris he was being duped.10 Anthon vehemently denied giving any kind of written approval. Elsewhere, however, Anthon convoluted his testimony by admitting that, when asked for his written opinion, he “did so without any hesitation,” offering what he believed to be an authoritative debunking.11 The characters were, in the professor’s opinion, meaningless “imitation of various alphabetic characters.”12 So, depending on who you trust, Anthon both did and did not write something down about the ‘Caractors.’

(Schrödinger’s cat would like a word.)

What really happened? We’ll never know for sure. If I had to guess: Anthon was mildly intrigued, gave a cautious “maybe,” and years later, once Mormonism took off, distanced himself to avoid professional embarrassment. In any case, Harris clearly did meet with Anthon, showed him the “Caractors” document (or something like it), and received a mixed response.

Naturally, most researchers are drawn to the oddities and contradictions in this story, but I find it far more interesting to consider how Joseph Smith approached existing scripture to explain and frame his own production of new scripture, i.e., Isaiah 29.

To Joseph, the meaning was obvious: only the unlearned could read what the learned couldn’t. Isaiah had foretold it. The sealed book passed by the scholar and (in Joseph’s view) landed in the hands of the farm boy. It wasn’t a coincidence, because Joseph saw a divine pattern, one in which ancient prophecy pointed forward to his own role. For him, the Bible wasn’t a record of what God had done; rather, it was a revelation of what God was doing.

I don’t think that’s the case, though.

Isaiah 29 on Its Own Terms

If Joseph was wrong about Isaiah 29, it wasn’t for lack of imagination.

Isaiah had described a book delivered to the learned and the unlearned, who were challenged to read it. “I cannot,” said one of them, “for it is sealed.” The other said, “I cannot, for I am not learned” (Isaiah 29:11–12). Joseph read that and saw Martin Harris and Charles Anthon and himself.

But what happens when we juxtapose Joseph’s interpretation against the text and context of Isaiah 29?

In its original context, the passage is prophetic judgment against Jerusalem, and then against her enemies. The chapter opens with a cry of “woe” to Ariel (v. 1), a nickname for Jerusalem meaning “Lioness of God.” The city had been faithful in form but not in heart. Her people offered sacrifices and celebrated feasts “year to year” (v. 1), but God wasn’t impressed. Instead, He planned to lay siege to them (v. 3). Their religion had become a performance, and their lifestyles showed it.

So judgment was coming.

Then comes the turn that sparked Joseph’s imagination:

“For the Lord has poured out upon you a spirit of deep sleep, and has closed your eyes, the prophets; and your heads, the seers, he has covered. And the vision of all this has become to you like the words of a book that is sealed…” (vv. 29:10–11a)

The point isn’t that someone will eventually break the seal; rather, it’s that no one in Jerusalem can, because God Himself has sealed it as an act of judgment. Their spiritual leaders were asleep. Their eyes were shut. They couldn’t read not because they lacked literacy; it was humility they lacked.

They drew near with their lips, but their hearts were far from God (v. 13).

Isaiah 29 is a prophetic rebuke, one meant to expose Israel’s spiritual blindness and to prepare for a redemptive act of God that would be so far-reaching and wholly of His own doing that it could only be called a miracle, i.e., the messianic mission (see Isaiah 29:13–14; cf. Matthew 15:7–9).

So, what follows the rebuke in Isaiah 29 is God’s gracious response: hope for a miraclous future work of God. He will do “a marvelous work and a wonder” (v. 14), which Christians throughout the ages have interpreted as the first incarnation, God sending His Son. Through His Messiah, God would overturn human wisdom, humble the proud, and rescue sinners (see Isaiah 66:2). This is exactly how the apostle Paul understood the passage: “For it is written, ‘I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the discernment of the discerning I will thwart’” (1 Corinthians 1:19; cf. Isaiah 29:14). The marvelous work is Christ crucified, i.e., the foolishness of the cross that exposes the limits of human wisdom and opens the eyes of the blind, both literally and spiritually (see Isaiah 35:5–6; 42:7; John 9:1–7; 1 Corinthians 1:18).

The passage, as it stands, leaves very little room to assume a far-futured prophet could read a sealed book. It’s about judgement with messianic hope. So, to read Isaiah 29 as a prediction of the Anthon episode is to miss the messianic redemption plot—ironically, the very thing the Book of Mormon claims to reveal.

That raises the question: Why did Joseph see himself in this passage?

I sincerely believe that early in his life Joseph was a serious student of the scriptures, raised in a Bible-saturated society and in a Bible-reading family. He was someone who genuinely believed scripture “contained the word of God.”13 So why, in 1828, did he break from traditional Christians modes of interpretation—from seeing Isaiah’s rebuke against Israel’s spiritual blindness—and instead imagining it as a cryptic endorsement of his prophetic mission?

The answer reveals something central about Joseph’s way of reading the Bible: he wasn’t reading as an exegete, like nearly all other Christians. He was reading as a seer, whether you believe him or not.

The Bible wasn’t a closed book of past fulfillment to Joseph; rather, it was more an open template for present revelation. So, to Joseph, Isaiah’s words pointed readers to the present day New York, not ancient Judah.

Like a prophet of old, Joseph looked into the pages of scripture and found a mirror, one that reflected his own story. The Book of Mormon was his “sealed book.” Martin Harris was the unlearned bearer. Charles Anthon was the wise man confounded.

It all fits together, if you squint hard enough. But if you read Isaiah on Isaiah’s terms, it doesn’t hold. Perhaps that’s the real marvel—Joseph’s remarkable interpretive leap. In retrofitting divine judgment as divine endorsement, he reshaped rebuke into revelation.

And that’s a pattern we see over and over in Joseph’s career: the Bible was less a fixed prescription for the Christian faith as it was a template to be restored. Joseph read himself into the story, reframed judgment as vindication, and repurposed ancient voices to narrate a new theology.

📘 Coming Soon: 40 Questions About Mormonism

If you’ve appreciated this essay, you’ll love my forthcoming book, 40 Questions About Mormonism (Kregel Academic, this coming winter). It’s written for traditional Christians who want clear, charitable, and biblically faithful answers to the most common questions about the Latter-day Saint faith and tradition.

Joseph Smith Papers, H1:15.

The image shown is a copy of the transcribed text made by David Whitmer, who claimed the document was the same one Martin Harris showed scholars in 1828. However, evidence suggests John Whitmer created it later, likely after meeting Joseph Smith in 1829.

John Turner, Joseph Smith: The Rise and Fall of an American Prophet, 45.

Joseph Smith Papers, H1:240.

https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/triple-index/anthon-charles?lang=eng

Charles Anthon, letter to Eber D. Howe, reproduced in Howe’s Mormonism Unvailed (1834), ed. Dan Vogel (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2015), 379–83. Emphasis original.

Dan Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, 4:380.

Ibid.

Sonia Hazard, “How Joseph Smith Encountered Printing Plates and Founded Mormonism,” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation, Vol. 31, Issue 2, pp. 137–92.

Howe, Mormonism Unvailed, 380.

Vogel, EMD, 4:384.

Vogel, EMD, 4:385.

JSP, H1:11.